Undoubtedly, our most famous wreck is that of La Girona, a galleous of the Spanish Armada, which, overladen with people and treasures, hit the rocks off the Giant’s Causeway in 1588 and sank.

Of the 1300 people on board, only 9 are believed to have survived and the treasures remained on the seabed until they were discovered by a team of divers from Belgium led by Robert Sténuit in the late 1960s.

Once a popular site for divers following Stenuit’s finds in the 1960s, the site is now designated under The Protection of Wrecks Act, 1973, which requires any diver visiting the site to have a licence. Therefore, the site does not feature on DiveNI and to be honest, by all accounts, there isn’t much to see down there anyway, apart from kelp!

However it is the story behind the Girona that is so famous, from its role in the Spanish Armada fleet to its floundering off the Giant’s Causeway and subsequent loss of life and finally, to the discovery of all the treasures that it carried some ~380 years later..

The Discovery of La Girona by Divers in the 1960’s

Robert Sténuit, a renowned diver, underwater explorer and salvage expert from Belgium, spoke to me prior to the launch of DiveNI about his career and that heartstopping moment when he discovered the remnants of La Girona.

“I started diving when I was very young, about 17 I think, as I began my explorations or, more correctly said, my strolls in the caves and caverns of the Belgian Ardennes. As many of them were inundated, I was forced over the years to use an aqualung every time I arrived at the bank of the flooded end of a cave system.”

Sténuit had a passion for history and was able to combine this with his love of diving. After reading 600 Milliards Sous les Mers by Harry Reiseberg, a story about shipwrecks and treasure diving, he left university and began his career working for the Atlantic Salvage Company Ltd. on the specially-equipped vessel Dios Te Guarde for search and recovery of underwater treasure.

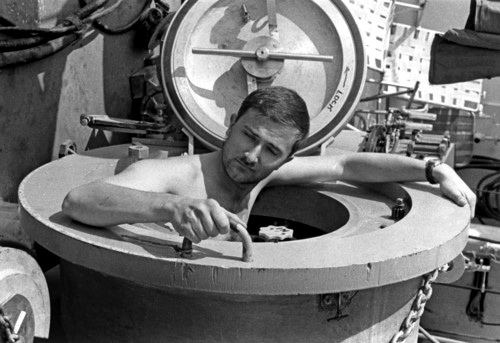

Later he became the chief diver for Edwin Link’s Man in Sea project. To quote Edwin Link, “the aim of ‘Man in Sea’ project was to enable men to work on the ocean floor for days, weeks and even months”. As part of the experiment, Sténuit was submerged in a cylinder at 200 metres, breathing a helium-oxygen mixture where he remained for 24 hours, becoming the world’s first ‘aquanaut’.

“Being under water for 24 hours was just great for the very young man I was then since I was very conscious, and rather proud, of achieving something that no one had attempted before me. As for the side effects, they were acceptably minor and did nor leave any trace after a while.”

Sténuit later fronted Ocean Systems in London, working on offshore oil and gas rigs in the North Sea but in his spare time, he began researching the wreck of La Girona.

“My interest in the Girona was sparked by the fact that I was at the time very enthusiastically studying the question of sunken treasures and the Girona was in fact a concentrate of treasures since she had on board, at the time of her loss, the cream of the officers and of the caballeros of two other armada ships that had been lost on the west coast of Ireland at about the same time and had saved all they could. “

“My research was made possible, as it is always the case, by the information that was available, not easily available, mind you, in the Spanish, English, Irish and French records of the time, which I had to comb patiently and with quite a degree of fervor.”

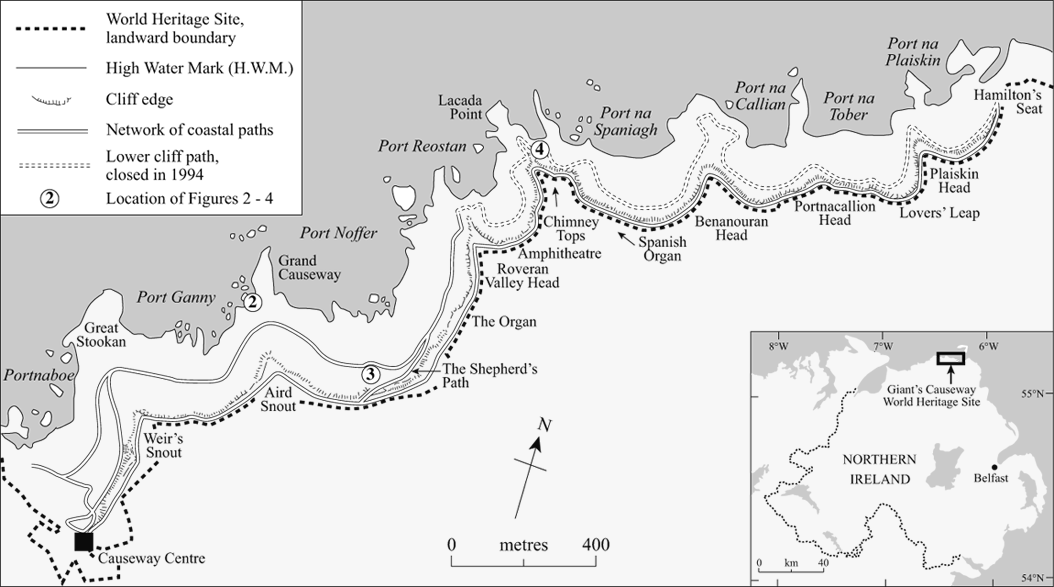

Knowing the story of the route of the Girona and its floundering somewhere on the north coast (from local accounts), Sténuit looked at old Ordnance Survey maps and noted ‘Lacada Point’, ‘Spaniard Rock’ and ‘Port na Spaniagh’ just beneath the Giant’s Causeway.

This led him and his team to Portballintrae in 1967 where he found lodgings in a local B&B. At the time, they kept their project a secret from the locals, telling them that they were in the area for scientific research.

“When we arrived in Portballintrae, I began my search where all the contemporary historical documents advised me to go and dive. That is just next to the Giant’s Causeway.”

“The Portballintrae locals were much interested by our activities and we soon developed very friendly ties with local amateur divers and with such local people as were interested in the history of their area.”

Following a number of fruitless dives, it was on 27th June 1967 that Sténuit found an object that he instantly recognised from other Armada wrecks and knew that he had finally found the site of La Girona.

“The first artefact from the Girona which I found was a large lead ingot, it was boat-shaped and covered with marks in Roman numerals that referred to its weight and featured also the initials of the merchant mark of their owner.”

“Having first found remnants of the wreck, I kept my discovery secret until I was able, on the next season, to organise a small but well equipped salvage expedition. This was made possible with the help of the COMEX company of Marseilles and by the enthusiasm of its president, the late Henri Delauze, who was himself a keen diver of course and a great fan of maritime history.”

Sténuit and his team left Portballintrae following their initial discoveries and went to London to formally register their interest in the site with the Receiver of Wrecks, providing them with the legal power they needed for their salvage operation the following summer.

“When we returned in 1968, the Portballintrae locals were still unaware of what I was looking for. “

“As we lifted the first cannon of the wreck the local divers and the local community were indeed quite interested and thrilled.”

The word was finally out and divers from across the country arrived in Portballintrae for the opportunity to explore the wreck. This resulted in some conflict, both above and below the water, but that story is for someone else to tell!

“I made three long stays in Portballintrae to complete the project in the years 1968, 1969 and 1970.”

“Among my enduring memories from that period of my life is the satisfaction, to put it in a very mild way, of having been able to do exactly what I wanted to do in the kind of adventurous life I had chosen when still very young.”

After the 3-year long salvage operation, the team found hoards of treasure including gold coins, chains, rings and pendants (including the famous Salamander), silver candlesticks and scent bottles.

Having researched all items onboard La Girona prior to his search, Sténuit knew to look for 12 lapis lazuli Cameos of Roman Emperors, however, he only found 11 and it wasn’t until 1998 that a local diver found the final 12th item.

In the end, after a lengthy court case following the salvage operation, the objects discovered by Sténuit and co on the site were valued at £132,000 and it was agreed that these would stay in Northern Ireland, where they remain on exhibition at the Ulster Museum. Some of these items are also listed on the Museum’s website.

We produced a short video telling the story of the Girona, its discovery and details about the treasures that were found:

Sally Stewart-Moore

DiveNI Creator